The Book of Acts

About

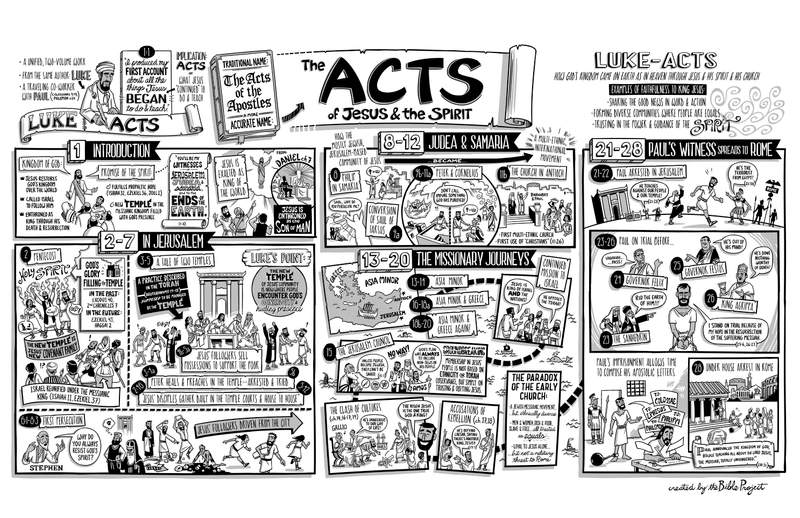

This is the second volume in the unified, two-part work that we know today as Luke-Acts. Both books were written by the same author, Luke, a traveling coworker to Paul (Col. 4:14). This is clear from the book’s introduction, in which Luke says, “I produced my first volume (that is, the Gospel) about all the things Jesus began to do and teach” (Acts 1:1). In this opening line, Luke is also giving a clue as to what the book of Acts will be about. In volume one, Jesus began “to do and teach,” and so volume two will naturally be about what Jesus continued to do and teach.

This leads to an interesting point about the book’s traditional, but not original, title, The Acts of the Apostles. While different apostles do appear throughout most of the stories, the only single character who unifies the story from beginning to end is Jesus, appearing personally or acting through the Holy Spirit. The book, therefore, could be more accurately named The Acts of Jesus and the Spirit.

Who Wrote the Book of Acts?

Context

Key Themes

- The power of the Holy Spirit given to human beings

- Jesus’ ongoing mission to Israel and the nations after his departure

- The self-giving faithfulness of the early Church

Structure

Acts 1: Jesus Commissions His Disciples and Ascends to Heaven

The book’s introduction recounts how the risen Jesus spent some 40 days with his disciples teaching them “about the Kingdom of God” (Acts 1:3), connecting back to the story of Luke’s gospel. There, Jesus claimed that he was restoring God’s Kingdom over the world, beginning with Israel. He called Israel to live under God’s reign by following him and was enthroned as the messianic King when he gave up his life, conquering death through his love. As such, the book of Acts begins with the risen King Jesus instructing the disciples about life in his Kingdom.

Jesus promises that the Spirit will soon come and immerse them with his personal presence, fulfilling one of the key hopes in the Old Testament Prophets. They promised that in the messianic Kingdom, God’s presence, or his Spirit, would take up residence among his people in a new temple, transforming their hearts (Isa. 32:15; Ezek. 36:26-27; Joel 2:28-32). Jesus says that when this happens, the Spirit will empower his disciples “to be my witnesses in Jerusalem, Judea and Samaria, and to the ends of the earth” (Acts 1:8).

From here, Jesus is taken up from their sight in a cloud. This is an image from Daniel 7 showing that Jesus is now being enthroned as the Son of Man who was vindicated after his suffering. He now shares in God’s rule over the world, which he will bring fully here on Earth when he one day returns.

The main themes and design of the book flow right out of this opening chapter. The book of Acts is about Jesus leading his people through the Spirit to go out into the world and invite all nations to live under his reign. The story will begin with that message spreading in Jerusalem (chs. 2-7), into the neighboring regions of Judea and Samaria full of non-Jewish people (chs. 8-12), and from there out to the nations and the ends of the earth (chs. 13-28).

Acts 2-7: Pentecost in Jerusalem and the Birth of the Church

The focus stays on Jerusalem in chapters 2-7, as Jesus’ followers wait in the city until the feast of Pentecost when Jewish pilgrims arrive from all over the ancient world. The Holy Spirit suddenly comes upon the disciples as a great wind, and something like flames appear over each person’s head. Together, the disciples start announcing and telling stories of “God’s mighty deeds” (Acts 2:11), speaking in all these languages that they didn’t know before. And remarkably, all the people gathered nearby understand their words perfectly.

Now, in order to see what Luke is emphasizing in this story, it’s crucial to see the Old Testament roots in the key images. First of all, the wind and fire are a direct allusion to the stories about God’s glorious, fiery presence filling the tabernacle and temple (Exod. 40:38; 2 Chron. 7:1-3). These images also recall the prophetic promises that God would come live, through his Spirit, in the new temple of the messianic Kingdom (Ezek. 43; Hag. 2). Here in Acts, God’s fiery presence comes to dwell not in a building but in his people. Luke is saying that the new temple spoken of by the prophets is actually Jesus’ new covenant family.

This connects to the second thing that Luke’s trying to say. The prophets promised that when God came to dwell in his new temple, he would reunify the tribes of Israel under the messianic king. This is when the good news of God’s reign would be announced to all nations (Isa. 11; Ezek. 37). Luke describes in detail the international, multi-tribe makeup of the Israelites who first responded to Peter’s message at Pentecost. The apostles start calling Israelites to acknowledge Jesus as their Messiah, and thousands do, forming new communities of generosity, worship, and celebration.

But not everyone’s celebrating. Luke also shows how Jesus’ new family quickly faced hostility from the leaders of Jerusalem. With a beautifully symmetrical design in chapters 3-5, Luke tells a tale of two temples. God’s new temple, the community of Jesus’ followers, are gathering “every day in the temple courts and from house to house” (Acts 2:46; Acts 5:42). Inside of these identical notices are two stories of Peter and other apostles healing people in the temple courts, only to be arrested by the temple leaders (Acts 3-4a, 5b). These arrests are followed each time by a speech from Peter, claiming that Jesus is the true King of Israel.

At the center of this symmetry are stories about Jesus’ followers who donate property and possessions to a common fund to help the poor (Acts 4:25-5:11). And this generosity is wonderful, but it seems random for Luke to mention it here. But Jewish readers would understand because, according to the laws of the Torah (Deut. 14-15), this practice was supposed to be happening through the Jerusalem temple and its leaders. Luke’s point is clear. The new temple of Jesus’ community is fulfilling the purpose God always intended for the Jerusalem temple, to act as a place where Heaven and Earth meet and where people encounter God’s generosity and healing presence.

This conflict between the temples culminates with the first wave of persecution in chapters 6-7. Jesus’ followers continue to multiply, requiring a new generation of leaders. One of them, Stephen, is a bold witness for Jesus in Jerusalem, but he ends up arrested and accused of speaking against and even threatening the temple (Acts 6:12-13). Stephen gives a long speech, showing how Israel’s leaders have always rejected the messengers God sent them, including Jesus and now his disciples. The Jerusalem leaders become enraged and murder Stephen, launching a wave of persecution against Jesus’ followers and driving most of them from the city. The crisis has a paradoxical effect, however. Luke shows how this tragedy actually becomes the means by which Jesus’ people are now sent out into Judea and Samaria, just as Jesus had planned (remember Acts 1:8).

Acts 8-12: The Jesus Community Becomes an International Movement

In the following section (chs. 8-12), Luke has collected a diverse group of stories that show how the mostly Jewish, Jerusalem-based community of Jesus became a multiethnic, international movement. The first story is about Philip’s mission into Samaria, which is the land of Israel’s hated enemies. Many come to know and follow Jesus (ch. 8). Next, we see the conversion of Saul of Tarsus, later and better known as Paul (ch. 9). He was the sworn enemy and even a persecutor of Jesus' followers until he personally met Jesus as the risen King. He went on to instead become a passionate advocate on Jesus’ behalf.

Next is a story about Peter (chs. 9-11), who has a dream-vision in which he learns that God does not consider non-Jewish people ritually impure or unworthy of joining Jesus’ family. Peter is led by the Spirit to the house of a Roman soldier, full of non-Jews, who all respond to the good news about Jesus. In this story, the Spirit shows up just as powerfully as he did for the Jewish disciples of Jesus in chapter 2.

These themes all culminate in the founding of the church at Antioch (ch. 11b), the largest, most cosmopolitan city in that part of the Roman empire. Luke tells us that Barnabas, a Jewish leader from the Jerusalem church, went along with Paul to help lead this church community. During their time there, it also became the first large multiethnic church in history, as well as being the location at which Jesus’ followers were first called Christians (Acts 11:26). From this church, the first international missionaries were sent out, and Jesus’ commission became a reality.

Acts 13-20: Mission to Israel and Clashes with Roman Culture

The church in Antioch became the flagship church of the first international Christian missionaries. Barnabas and Paul were serving in this church and were prompted by the Spirit to leave, opening the second main section of the book of Acts (chs. 13-20). Paul and various coworkers travel around the Roman empire to announce the good news that Jesus is King. The first journey starts in the interior of Asia Minor (located in modern day Turkey) and ends with an important meeting of the apostles back in Jerusalem (ch. 15). The second trip is through Asia Minor and into ancient Greece (chs. 16-18a), and the third trip goes through the same territory once again, concluding with Paul’s journey back to Jerusalem (chs. 18b-20).

In recounting these stories, Luke has highlighted a number of key themes through repetition, beginning with the continued mission to Israel. Upon entering a new city, Paul always first visits the Jewish synagogue to share how Jesus is the risen King who is now forming a new multiethnic people of God. Many Jewish people come to recognize Jesus as their Messiah. Others, however, oppose Paul and sometimes even run him out of town as a dangerous rebel who opposes the Torah and Jewish tradition.

This tension culminates after the first journey and leads to an important council in Jerusalem (ch. 15). Paul discovers that there are some Jewish followers of Jesus in Antioch claiming that unless non-Jewish people become Jewish by practicing circumcision, the Sabbath, and obeying kosher food laws, they can’t be a part of Jesus’ redeemed people. Paul and Barnabas radically disagree with this claim, so they take the debate to a leadership council in Jerusalem. There, Peter, Paul, and James, the brother of Jesus, discuss and discern from the Scriptures and from their experience that God’s plan was always to include the nations within his covenant people. While they do require non-Jewish Christians to stop participating in pagan temple sacrifices, they don’t require them to adopt an ethnically Jewish identity or become Torah-observant.

This decision was groundbreaking for the history of the Jesus movement. Jesus, who is the risen King of all nations, is an ethnically Jewish Messiah. However, a person’s membership among his people is not based on ethnic identity or Torah observance. Instead, one must simply trust in Jesus and follow his teachings.

It’s this multiethnic reality of the Jesus movement that leads to the next theme Luke emphasizes, namely, the clash of cultures between the early Christians and the Greek and Roman world.

Luke records multiple clashes in Philippi, Athens, and Ephesus (chs. 14, 16-17, 19). Paul announced Jesus as the revelation of the one true God who is the King of the world. The implication of this claim is that all other gods and idols are powerless and futile. This message was consistently viewed as subversive to the Roman way of life, and Paul was accused of being a dangerous social revolutionary. These stories show how the multiethnic, monotheistic Jesus communities didn’t fit into any cultural boxes familiar to the Romans. The ancient world had simply never seen anything quite like these Christian communities.

Even more to the point, Luke makes clear that the Christians aroused more than just suspicion. Multiple stories show Romans accusing Paul and the Christians of rebellion and treason against Caesar. And it’s understandable. People were hearing Paul correctly when he announced that “there was another king, Jesus” (Acts 17:7), and they correctly saw the Christian way of life as a challenge to many Roman cultural values. But every time Paul is arrested and interrogated by Roman officials, they can’t see any threat, and they end up releasing him.

All of these themes show the paradox that the early church presented to the world. It was a Jewish messianic movement made up of ethnically diverse communities. Men and women, rich and poor, slave and free were all treated as equals because they all gave their allegiance to King Jesus alone and to no other god or king. Their very existence subverted the core values of Roman culture, yet they posed no military threat because Jesus had taught them to be a people of peace. Really, the only crime that they could be accused of was not conforming to the status quo.

Acts 21-28: Paul Arrested in Jerusalem and Imprisoned in Rome

The book of Acts’ final section, chapters 21-28, returns the focus to Paul’s witness spreading from Jerusalem to Rome. His final missionary journey ends in Jerusalem, where his controversial reputation precedes him. Paul is attacked by Jewish people who think that he has betrayed Israel, attracting the attention of Roman soldiers. These soldiers in turn think that Paul is a terrorist from Egypt who is starting a rebellion, so they arrest him. Paul is put on trial before the Jewish leaders of the Sanhedrin in Jerusalem (ch. 23) as well as before a series of Roman leaders in Caesarea. Governor Felix only puts Paul off for the next governor, Festus, who eventually brings Paul before King Agrippa (chs. 24-26). Paul ends up in prison for years even though each trial fails to declare him guilty. All he’s doing is announcing that his hope in the resurrection has been fulfilled through King Jesus. It’s hardly a crime, but at this point, the Roman legal machine can’t just let him go, so Paul appeals to Rome's highest court.

Now, all this prison time would seem like a setback for Paul, whose passion was to go on the road and start new Jesus communities. But in this story, the Spirit orchestrates all things for good. The prison time allows Paul to write his most important apostolic letters—Ephesians, Philippians, Colossians, Philemon—and these become the way his missionary legacy was carried on into history. Eventually, Paul was transferred as a prisoner to Rome and, after a terrifying and near-death voyage across the Mediterranean, he ends up under house arrest in Rome, awaiting his delayed trial. From there, he hosts regular meetings that reach both Jews and Gentiles. The book ends with Paul “announcing the Kingdom of God and boldly teaching all about the Lord Jesus Messiah, totally unhindered” (Acts 28:31)—right under Caesar’s nose in Rome.

The unified works of Luke and Acts do so much more than give a history of Jesus and the early Church. They tell the story of how God’s Kingdom arrived here on Earth as in Heaven. It began with Jesus’ life, death, and resurrection, and it continued through the coming of his Spirit to empower Jesus’ followers to bear witness from Jerusalem to the ends of the earth. In telling this story, Luke has also given us scores of examples of what faithfulness to King Jesus looks like. It means sharing the good news of the risen King through words and actions. This results in the formation of diverse communities in which people of all kinds are treated equally, as they give their allegiance to Jesus and live by his teachings. And threading all of this together is the power and guidance offered by the Spirit, who leads the Church beyond chapter 28 and continues the story even today.