The Book of Exodus

Exodus is the second book of the Bible, and it picks up the biblical storyline right where Genesis left off. Abraham’s grandson Jacob and his family of seventy made their way down to Egypt, where Joseph, one of Jacob’s sons, had been elevated to second in command over Egypt. So the family lived and grew in Egypt as a safe haven for many years.

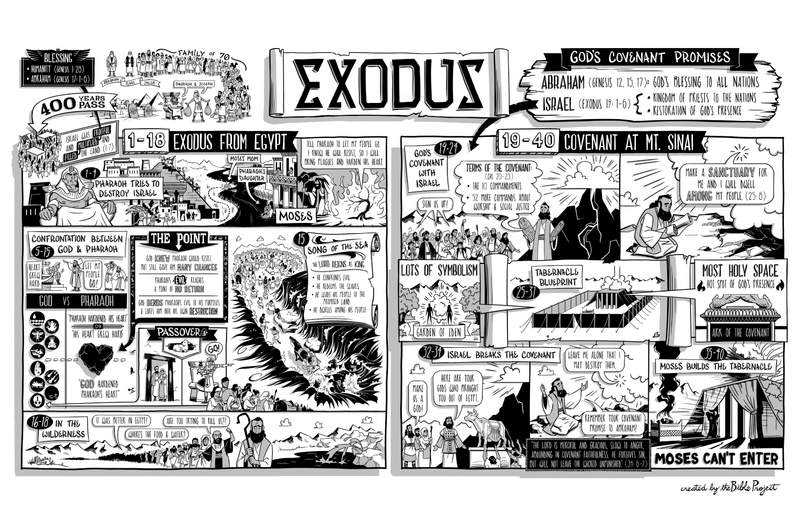

After a few hundred years, the story of Exodus begins.The word “exodus” refers to the major event that takes place in the first half of the book, Israel’s exodus from Egypt. The book also has a second half that takes place at the foot of Mount Sinai. For now, we will focus on the first half, in which centuries have passed and the Israelites “were fruitful and multiplied and filled the land” (Exod. 1:7).

This phrase is a deliberate echo of the blessing God gave humanity back in the garden (Gen. 1:28), which reminds us of the bigger story so far. When humanity forfeited God’s blessing through sin and rebellion, God’s response was to choose Abraham’s family as the vehicle through which he would restore his blessing to the world.

Who Wrote the Book of Exodus?

Context

Key Themes

- God’s confrontation with evil brings justice and rescue

- God’s desire and plan to dwell among his people

- God’s faithfulness to his promises and commitment to an often faithless people

- Sin and idolatry as the greatest threats to the covenant promises and blessings

Structure

Exodus 1-4: Israel’s Enslavement Under Pharaoh

The new Pharaoh, however, does not see Israel as a blessing. He thinks this growing Israelite immigrant group is a threat to his power. So, just as in Genesis, humanity rebels against God. Pharaoh attempts to destroy the Israelites by brutally enslaving them and using them in hard physical labor. It’s bad, but it gets worse when he orders that all Israelite boys be drowned in the Nile River.

This Pharaoh is the worst character in the Bible so far, and his kingdom epitomizes humanity’s rebellion against God. Pharaoh has so redefined good and evil according to his own interests that murder of innocent children becomes “good.” Egypt has become worse than Babylon, and Israel cries out for help against this new form of evil. God responds by first turning Pharaoh’s evil plot upside-down. An Israelite mother throws her boy into the Nile, protected inside a basket, and the child floats right into the Pharaoh’s own family. This boy is named Moses, and he eventually grows up to become the man God will use to defeat Pharaoh.

In the famous story of the burning bush, God appears to Moses and commissions him to go to Pharaoh and order him to release the Israelites. God says that he knows Pharaoh will resist. But God plans to bring his justice down upon Egypt in the form of plagues and harden Pharaoh’s heart.

Exodus 5-15: The Ten Plagues and Pharaoh’s Hardening Heart

The confrontation between God and Pharaoh is the major focus in this narrative, but what does it mean that God will harden his heart? It is important to read this part of the story closely and in sequence. In Moses and Pharaoh’s first encounter, we are told simply that Pharaoh’s heart “grew hard,” without any implication that God caused it.

God proceeds to send the first set of five plagues, each one confronting Pharaoh and his gods. Each time, Moses offers a chance for Pharaoh to humble himself and let the people go. However, after each plague, we are told that Pharaoh either “hardened his heart,” or that his “heart grew hard.” He’s doing this of his own will. It’s only with the second set of five plagues that we begin to hear that God hardened Pharaoh’s heart.

The point is that even though God knew Pharaoh would resist his will, God still offered him many chances to do the right thing. Eventually Pharaoh’s evil reaches a point of no return, and even his advisors think he has lost his mind. It’s at that point that God takes over and bends Pharaoh’s evil to his own redemptive purposes. He lures Pharaoh into his own destruction and saves his people.

With the final plague, the night of Passover, God turns the tables on Pharaoh. Just as Pharaoh killed the sons of the Israelites, so God will kill the firstborn sons of Egypt. Unlike Pharaoh, however, God will provide a means of escape through the blood of a lamb.

Here the story stops and introduces us to the annual Israelite ritual of Passover (Exod. 12-13). On the night before Israel left Egypt, they sacrificed a young, spotless lamb and painted its blood on the doorframe of their house. When the divine plague came over Egypt, the houses covered with the blood of the lamb would be “passed over” and the sons spared. Every year since, the Israelites have reenacted this night to remember and celebrate God’s justice and mercy.

Because of his pride and rebellion, Pharaoh loses his son and is compelled to finally let the Israelites go free. The Israelite slaves make their escape from Egypt, but as soon as they leave, Pharaoh changes his mind. He gathers his army and chases after them for a final showdown, thinking that he will slaughter them by the waters of the sea. However, the Israelites run into the sea and discover they’re walking on dry ground that God has provided. But when Pharaoh pursues them, the waters surge around him, destroying him.

This part of the book of Exodus concludes with the first song of praise in the Bible, called “The Song of the Sea” (Exod. 15). The final line declares that “the Lord reigns as king,” and the song retells in poetry what the God’s Kingdom is all about. God is on a mission to confront evil in his world, redeem those enslaved to evil, and bring them to the promised land where his divine presence will live among them. This is what it looks like when God becomes King over his people.

Exodus 16-18: Grumbling in the Wilderness

After the people sing their song, the story takes a surprising turn. The Israelites trek through the wilderness on their way to Mount Sinai and get really hungry and thirsty. In their distress, they start criticizing Moses and God for rescuing them from Egypt! Even though God graciously provides food and water for his people, these events cast a dark shadow. As readers, we wonder if it is possible that Israel’s heart is as hard as Pharaoh’s. We’re left with that haunting question as we turn to read about Israel’s experience at Mount Sinai.

Exodus 19-31: The Covenant at Sinai

The second half of the book of Exodus picks up right as Moses leads Israel to the foot of Mount Sinai (Exod. 19), where God invites the nation to enter into a covenant relationship. It’s here that we reach another key moment in the big storyline of the Bible. This moment develops God’s promise to Abraham—that through him and his family God would restore his blessing to all nations (Gen. 12; Gen. 15; Gen. 17). God says that if the people of Israel obey the terms of the covenant, they will become a “kingdom of priests” (Exod. 19:6), acting as God’s representatives to the nations and showing them his character by how they live. In this way, God’s justice and mercy will reach the nations.

The people eagerly accept the offer, and God’s presence appears on the mountain in the form of a cloud. Moses goes up as the people’s representative, and God opens with the basic terms of the covenant, the famous Ten Commandments. These are foundational rules that set up how the Israelites relate to God and to each other. After this comes a collection of fifty-two more commands, which expand on the first ten with more detail. There are laws about Israel’s worship and social justice, which shape how Israel was to live differently from the other nations. Moses wrote down all these laws and brought them to the people, who eagerly agreed to the terms of the covenant.

God then takes the relationship forward another step. He tells Moses that he wants his holy and divine presence to dwell in the midst of Israel. This develops another aspect of God’s original covenant promise from the book of Genesis. After humanity’s rebellion in the garden, access to God’s presence was lost. However, through the family of Abraham, God’s presence has become accessible again, first to Israel at Mount Sinai and one day to all nations.

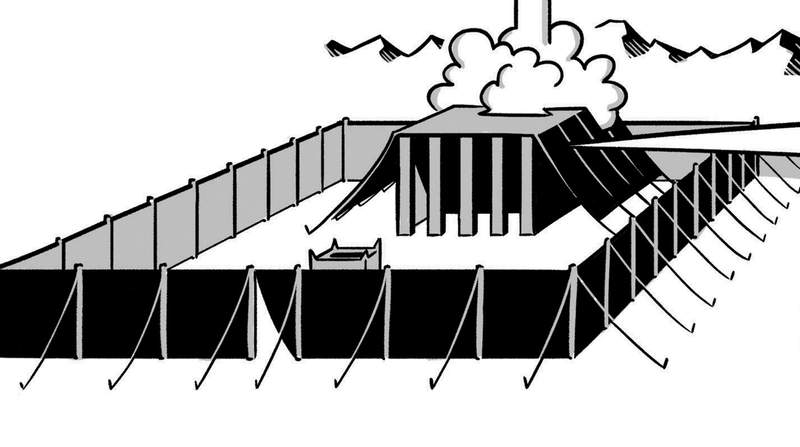

The following seven chapters (Exod. 25-31) detail the architectural blueprints of a sacred tent called the tabernacle. There is an outer courtyard with an altar, an outer and inner room in the center of the tent, and inside the inner room—called the most holy space—is a golden box with angelic creatures on it, the ark of the covenant. This ark acts as a “hotspot” for God’s presence.

There’s a lot of detail in these chapters, but it’s important to know that every part has a symbolic value. All of the flowers, angels, gold, and jewels call back to the garden of Eden, the place where God and humans lived together in intimacy. In other words, the tabernacle is a portable Eden where God and Israel can live together in peace. That’s how it could have worked, in theory, but things go off course, and Israel breaks the covenant.

Exodus 32-40: Israel’s Wilderness Rebellion

While Moses is up on the mountain receiving the blueprints for the tabernacle, the Israelites are losing patience down in the camp. They ask Moses’ brother Aaron to make a golden calf idol so they can worship it as the god who saved them from slavery in Egypt. Even as God’s presence is hovering atop the mountain, they are already breaking the first two commandments of the covenant: no idols and no other gods.

What follows is crucial to the rest of the biblical story and how we understand God’s character. God first invites Moses into his anger and pain, venting his feelings and saying he wants to wipe out the entire nation of Israel. After listening, Moses intercedes by appealing to God’s character, saying that this would mean going back on his covenant promises to Abraham. Moses also appeals to God’s reputation among the nations. What would the Egyptians think if he allowed Israel to die in the wilderness? God accepts Moses’ prayer and relents. And while God does bring justice to those who instigated the idolatry, he forgives the nation as a whole and renews the covenant. It’s at this point God describes himself to Moses. “The Lord is merciful and gracious, slow to anger, abounding in covenant faithfulness. He forgives sin, but will not leave the wicked unpunished” (Exod. 34:6-7). In other words, God is full of mercy, but he must deal with evil if he claims to be good. Above all else, God is faithful to his promises even if it means committing himself to people who are faithless.

After renewing the covenant, God commissions Moses to build the tabernacle, detailed in the next five chapters (Exod. 35-39). It all comes together in the final chapter (Exod. 40). The tabernacle is finished, and God’s glorious presence comes over the tent. Our hopes are high! But as Moses goes to enter the tent, he finds that he is unable to. He is blocked from entering, and the book of Exodus comes to a sudden end.

We see now that Israel’s sin has damaged their relationship with God in more ways than we had realized. The book may have opened with Pharaoh’s evil threatening Israel, but as the book comes to an end, Israel has become their own worst enemy. The sin and idolatry of God’s own people is now the greatest threat to his covenant promises. How is God going to reconcile the conflict between his holy, good presence with the sin and corruption of his own people? That’s the question that the next book, Leviticus, sets out to answer.

Frequently Asked Questions

Here are some of the most common questions people ask online about this book.

The book of Exodus establishes a pattern of salvation that repeats throughout the Bible. When God delivers his people from slavery in Egypt, he reveals his continual desire to rescue people from oppression and death. And Exodus shows that God’s ultimate aim of deliverance is to invite people to live in his presence. After God brings the Israelites out of Egypt, he enters into a covenant relationship with them; he gives them wisdom to live in ways that reflect their identity as his people. He also calls them to build a portable tent, the tabernacle, where he can dwell among them as they travel through the wilderness toward the land he promised their ancestors.

The Exodus pattern finds its ultimate fulfillment in Jesus. His life, death, and resurrection chart a path for his followers out of death and into the new promised land, the kingdom of the skies. When the Son of God becomes human, John 1:14 says that he “dwelt among us,” using a verb (skenoo) that’s related to the Greek word for the “tabernacle” (skene). In other words, Jesus becomes the new tabernacle, where God’s presence dwells among his people. And he establishes a “new covenant” (Luke 22:20), inviting everyone to enter into a covenant relationship with him so that they may follow his footsteps into new life.

While the Bible does not explicitly state why God chooses Moses to lead the Israelites out of slavery in Egypt, it does provide insight into why Moses is an ideal candidate for this role. Moses’ life experiences closely parallel and foreshadow Israel’s exodus, making him uniquely suited to lead them.

As an infant, Moses faces death when Pharaoh declares that all the Israelite baby boys should be thrown into the Nile River (Exod. 1:22). Moses’ mother eventually complies with Pharaoh’s command, but places him in a protective “ark” (Hebrew tevah, Exod. 2:3; see Gen. 6:14). He is then rescued from the waters of death when Pharaoh’s daughter draws him out of the river and adopts him as her son. Having already experienced God’s exodus deliverance himself, Moses should now trust that God could also rescue Israel.

While Moses is still in Egypt, he shows compassion towards the plight of his people when he kills an Egyptian overseer beating an Israelite slave (Exod. 2:11-12). His desire is to rescue his people, but his action shows a lack of judgment. He doesn’t seek God’s will about when and how God plans to bring about deliverance.

Although Moses’ experiences and character traits uniquely qualify him for the job of leading the Israelites, he is reluctant to accept it. So God assures Moses that he will be with him (Exod. 3:11-12). Moses will deliver the people, not by his own strength, but through God’s mighty power.

After God calls Moses to lead the Israelites out of Egypt, Moses asks God for his name. In the ancient world, names reflected a person’s identity and character. So God answers, “I am (Hebrew ’ehyeh) who I am (’ehyeh)” (Exod. 3:14), which is related to God’s revealed name: Yahweh.

The Hebrew verb hayah, which appears in both forms of God’s name, reflects his continual, self-sustaining, and unchanging existence. His being doesn’t depend on anyone or anything. He simply is. He’s the one who brings everything else into being, and his character is consistent and dependable.

“I am who I am” is also deeply connected to God’s desire to be with his people. When Moses first hears God’s challenging call, he’s reluctant. How could he, an exiled shepherd, free an enslaved nation from a major world power like Egypt? God is patient with his doubts and fears, declaring, “I will be (’ehyeh) with you” (Exod. 3:12). By using a part of his name in his promise to Moses, God emphasizes that this promise is a commitment engraved in his identity and character. He is the God of exodus, who faithfully frees his people from oppression and brings them to life with him.

When God calls Moses to go and save the Israelites from their oppression in Egypt, Moses doubts the people will believe God has sent him. So God gives Moses three signs to demonstrate his authority. First, he instructs Moses to throw his staff on the ground, and it turns into a snake, leading Moses to run away in fear. But God invites him to “reach out” (shalakh) his hand and pick up the snake by the tail. And when he does, the snake turns back into a staff. Picking up the snake by the tail is risky, as it leaves the head free to strike. So Moses’ action reflects his trust that God will protect him. But it also symbolizes something much more profound.

In ancient Egypt, the Pharaoh was often connected with the image of a snake; his headdress displayed the Uraeus—a cobra. In God’s instruction for Moses to “reach out (shalakh)” his hand and pick up the snake, God deliberately repeats the language of his earlier promise to Moses: “I will reach out (shalakh) my hand and strike Egypt with all my miracles which I shall do in the midst of it; after that he will let you go.” (Exod. 3:20, NASB) By inviting Moses to stretch out his hand against the snake, God shows that he is giving Moses authority over Pharaoh and partnering with Moses to fulfill his promise.

In the Bible, the snake-like Pharaoh also parallels the snake in Genesis 3, who embodies evil and rebellion against God. As Moses reaches out his hand against the snake, he becomes one fulfillment of God’s promise that Eve’s offspring will crush the head of the snake (Gen. 3:15).

After God calls Moses to return to Egypt and free his people from slavery, God meets Moses on the way and seeks to kill him (Exod. 4:24-26). But why would God kill his own messenger?

There are two primary possibilities. The first possibility is Moses’ failure to circumcise his son Gershom. As a descendant of Abraham, Moses and the whole community of Israel are bound in covenant relationship with God. At this point in the story, the Israelites must observe just one practice in order to participate in this covenant: circumcision. Anyone who does not circumcise their son is to be cut off from the community (Gen. 17:9-14). So how can Moses take on the role of Israel’s leader if he won’t circumcise his own son?

The second possible reason for the threat to Moses’ life is his past. Before he flees from Pharaoh, Moses kills an Egyptian (Exod. 2:12). God has already made clear that there are life-for-life consequences for those who murder (Gen. 9:5-6). In fact, the consequences for taking someone’s life are clear in the surrounding story. God has just said that he will kill Pharaoh’s firstborn son in return for Pharaoh’s murder and mistreatment of the Israelite people (Exod. 4:22-23; see 1:8-22). Now Moses, too, is guilty of bloodshed. When Pharaoh hears about Moses killing an Egyptian, he “seeks” (baqash) to kill Moses, who then escapes to Midian (Exod. 2:15). So when God seeks (baqash) to put Moses to death, he may be confronting him for a crime that has not yet been dealt with.

But Zipporah, Moses’ wife, addresses both of these problems by quickly circumcising her son. Though she is not an Israelite, she clearly understands the significance of circumcision for God’s covenant community. And when Zipporah sheds blood and “touches” (naga‘) her son’s foreskin to Moses’ feet, her actions point forward to the Passover. When the blood of the Passover lamb touches (naga‘) the doorposts of the houses, those inside the house are protected from God’s judgment on Pharaoh for his murderous actions.

The tabernacle is a portable temple where God’s presence dwells with Israel during their journey through the wilderness. After freeing the Israelites from slavery in Egypt, God gives Moses instructions for building the tabernacle at Mount Sinai (Exod. 25-31). Once the tabernacle is completed, God’s presence comes down from the top of the mountain to dwell in this carefully crafted structure (Exod. 40:34-35).

The tabernacle is divided into three parts, each designed for a different purpose. The outer courtyard provides a place for people to bring their offerings to God. Within this courtyard is the holy place, which only priests can enter to fulfill their responsibilities. And beyond the holy place is the holy of holies, where God’s presence is concentrated. Only the high priest can enter this inner room, and only once a year on the Day of Atonement (Lev. 16).

The tabernacle is designed intentionally to evoke the garden of Eden. The tabernacle’s lampstand, with its branches and blossoms (Exod. 25:31-40), recalls the tree of life. And the cherubim that sit in the holy of holies (Exod. 25:16-22) are like the cherubim that guard the entrance to the garden after the humans are expelled (Gen. 3:24). Also, God gives Moses instructions for the tabernacle in seven speeches, echoing the seven-day creation account. These connections make it clear that the tabernacle, just like the garden, is a Heaven-on-Earth space, where God’s presence dwells with his people.

In Exodus 25-31, God gives Moses detailed instructions for the tabernacle. And a few chapters later (Exod. 35-40), many of the same details are repeated when the people build the tabernacle. In order to understand why the book includes all this repetition, it is helpful to take a look at the narrative that takes place in between (Exod. 32-34).

When Moses comes down from Mount Sinai with the blueprint for the tabernacle, he finds the people of Israel worshiping a golden calf (Exod. 32:1-19). After agreeing to step into a special covenant relationship with God (Exod. 19:4-8), they break that covenant almost immediately by making an idol (see Exod. 20:4-6). This threatens the Israelites’ ability to live in God’s presence and puts the construction of the tabernacle on hold. Will God still choose to dwell with them?

Moses prays on behalf of the people, and, despite their failure, God reestablishes his covenant relationship with them (Exod. 34:27-28). So Exodus 35-40 celebrates that the Israelites are able to move forward with building the tabernacle so that God’s presence may come down to dwell in their midst.

In Exodus 34:6-7 God describes himself this way:

“Yahweh, Yahweh,

a God compassionate and gracious,

slow to anger,

and abounding with loyal love and faithfulness,

keeping loyal love to the thousands,

forgiving iniquity and transgression and sin,

though he does not totally declare innocent [the guilty],

visiting the iniquity of fathers on sons, and on sons of sons,

to the threes and the fours.” (BibleProject Translation)

These words come at a crucial moment in Israel’s story. The people have just accepted God’s invitation into a covenant relationship. But then they break their commitment by worshiping an idol. How will God respond to the people’s unfaithfulness?

In the midst of this uncertainty, God describes his character to Moses. And then he demonstrates his compassion, grace, loyal love, and faithfulness by renewing his covenant with Israel (Exod. 34:27-28). Even after the people fail to keep their promise, he continues to offer a covenant relationship with them.

For some of us, the final line of this poem may raise the question: Will God unfairly judge children for their parents’ choices? But other passages, like Deuteronomy 24:16 (NASB), make it clear that God does not punish the innocent for the offenses of the guilty: “Fathers shall not be put to death for their sons, nor shall sons be put to death for their fathers; everyone shall be put to death for his own sin alone.”

God’s self-description reveals that he takes human acts of injustice and unfaithfulness seriously. And it reminds us that harmful behavior is often passed down from one generation to the next. But while God addresses wrongdoing, the passage emphasizes that his loyal-love and forgiveness extend far beyond his judgment, to the thousands.

These words describing God’s character are so important that they are alluded to throughout the rest of the Bible more often than any other passage (see, for example, Deut. 5:9-10; Ps. 86:15; Dan. 9:4). So Exodus 34:6-7 gives us a key introduction to God’s character.