The Book of Luke

About

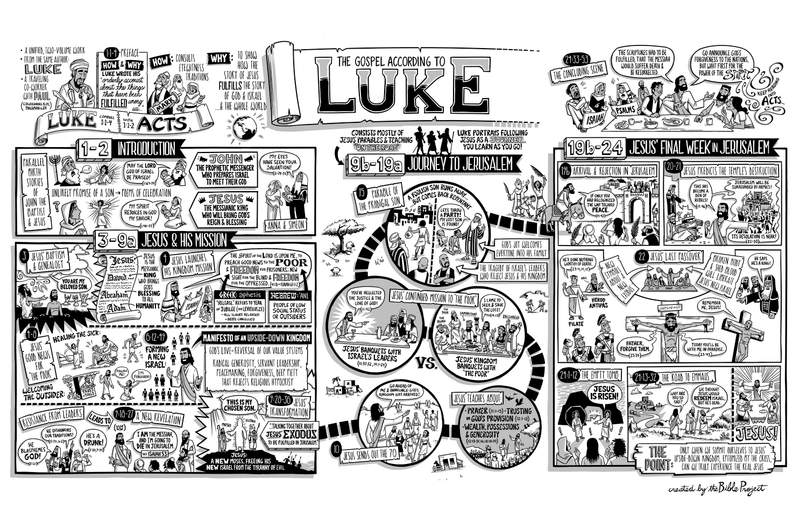

The book of Luke is another one of the earliest accounts of Jesus’ life, and it’s actually part 1 of a unified, two-volume work called Luke-Acts. If you compare the opening lines of both books, it’s clear that they come from the same author (Luke 1:1-4; Acts 1:1-2). There are internal clues in Acts and also in early tradition that identify the author as Luke, a doctor as well as the traveling companion and coworker of Paul the apostle (Col. 4:14; Phm. 1:24).

Luke opens with a preface (Luke 1:1-4) to tell us how and why he wrote the book. While he acknowledges that other fine accounts of Jesus’ life are out there, he wanted to go back to the eyewitness traditions of as many early disciples as he could in order to produce what he calls “an orderly” account about “the things that have been fulfilled among us.” That word “fulfilled” shows us why Luke produced this volume. For him, the story of Jesus isn’t merely ancient history. He wants to show how it’s the fulfillment of the long covenant story of God and Israel and, on a larger scale, the story of God and the whole world.

The book’s design is fairly clear. There’s a long introduction in chapters 1-2, setting up the stories of John the Baptist and Jesus. In chapters 3-9, Luke presents a robust portrait of Jesus and his mission in his home region of Galilee. After that, the large midsection of the book (Luke 9:51-19:27) contains Jesus’ long journey to Jerusalem, leading into the story’s climax (Luke 19:28 through the final chapter), Jesus’ final week in Jerusalem that leads to his death and resurrection. This in turn leads on into the book of Acts.

Who Wrote the Book of Luke?

Context

Key Themes

- The upside-down Kingdom of God

- Israel’s freedom and new covenant

- God’s faithfulness to his people seen in his human incarnation

Structure

Luke 1-2: The Birth of Jesus and John the Baptist

The extended introduction in chapters 1-2 recounts, in parallel, the birth stories of both John the Baptist and Jesus. An elderly, priestly couple (Zechariah and Elizabeth) and a young, unmarried woman (Mary) both receive an unlikely divine promise that they’ll have a son. Both promises are fulfilled as John and Jesus are born, and both parents sing poems of celebration.

These songs are filled with echoes from the Psalms and Prophets in the Old Testament, and they show how these children will fulfill God’s ancient promises. The poems also preview each child’s role in the story to follow. John is the prophetic messenger promised in the Torah and Prophets, who will prepare Israel to meet their God. Jesus is the messianic King promised to David, who will bring God’s reign over Israel and his blessing to all the nations, just as was promised to Abraham.

Mary brings Jesus to the Jerusalem temple for his dedication, where two elderly prophets, Anna and Simeon, see Jesus and recognize who he is. Simeon sings a poem of his own that’s inspired by the prophet Isaiah. This child is God’s salvation for Israel, and he will become a light to the nations.

Luke 3:1-9:50: Jesus and the Upside-Down Kingdom of God

With all this anticipation, the story moves forward into the next main section with chapters 3-9, in which Luke presents Jesus and his mission. Luke sets the stage with John’s renewal movement at the Jordan River, calling a new, repentant, and recommitted Israel into existence through baptism. He is preparing for the arrival of the Kingdom of God. Jesus appears as the leader of this new Israel. He’s marked by the Spirit and the voice of God from heaven announcing that he is the beloved Son of God.

After this, Luke follows up with a genealogy that traces Jesus’ origins all the way back to David, then back to Abraham, and finally back to Adam from Genesis. Luke’s claiming here that Jesus is the messianic King of Israel, who will bring God’s blessing not only to Israel, the family of Abraham, but to all the descendants of Adam—all humanity.

Next, Luke has strategically placed the story of Jesus going to his hometown Nazareth (ch. 4), where he launches his public mission. At a synagogue gathering, Jesus stands up and reads from the scroll of Isaiah: “The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, to preach good news to the poor and freedom for prisoners; new sight for the blind, and freedom from the oppressed” (Luke 4:18, quoting from Isa. 61:1-2).

Along with the other Gospel accounts, Jesus is presented as the messianic King, bringing the good news of God’s Kingdom. What Luke uniquely highlights here, however, are the social implications of Jesus’ mission. He brings “freedom” (the Greek word is aphesis), which literally means “release.” The term refers to the ancient Jewish practice of the year of Jubilee (Lev. 25), when all Israelite slaves were released, people’s debts were canceled, and sold land was returned to families. This was all a symbolic enactment of God’s liberating justice and mercy.

Jesus says that this good news of release is specifically for “the poor.” Now, in the Old Testament, the poor (the Hebrew word is ani) has a broader meaning than just those who don’t have much money. It can refer to people of low social status in their culture, like people with disabilities, women, children, or the elderly. It also includes social outsiders, like people of other ethnic groups or those whose poor life choices have placed them outside acceptable religious circles. And surprisingly, Jesus says that God’s Kingdom is especially good news for these people.

Luke immediately goes into a large block of stories showing what Jesus’ “good news for the poor” looks like in reality (chs. 4-8). We watch Jesus heal a bedridden sick woman (Luke 4:38-39), people with skin disease (Luke 5:12-16), and those who are paralyzed (Luke 5:17-26). There are also stories about Jesus welcoming into his community a tax-collector, Levi (Luke 5:27-32), who’s not financially poor but is a social outsider. There is also a story about Jesus forgiving a prostitute (Luke 7:36-50). Luke is showing how Jesus’ Kingdom brought restoration and the reversal of people’s entire life circumstances. By doing so, Jesus expands the circle of people who are invited to discover the healing power of God’s Kingdom.

As his mission attracts a large following, Jesus does something provocative by forming them into a new Israel, appointing the twelve disciples as leaders, a clear symbol of Israel’s original twelve tribes (Luke 6:12-16). Jesus teaches them his manifesto of an Upside-Down Kingdom, often called the Sermon on the Plain (Luke 6:17-49). God’s love for the outsider and the poor means that his Kingdom brings a reversal of our value systems. He’s here to form a new, alternative people of God who respond to Jesus’ invitation by practicing radical generosity and serving the poor. Jesus’ disciples lead by serving and live by peacemaking and being deeply pious but rejecting religious hypocrisy.

Eventually, Jesus’ radical Kingdom vision and his claim to divine authority start to generate resistance and controversy, specifically from Israel’s religious leaders. His outreach to questionable people is a threat to their religious traditions (Luke 5:33; Luke 6:2) as well as their sense of social stability. They accuse Jesus of blaspheming God, mixing with sinners, and being a drunk (Luke 5:21; Luke 5:30; Luke 7:33).

This section culminates in a new revelation of Jesus’ mission to his disciples (Luke 9:18-36). Jesus says that he is the messianic King and will assert his reign over Israel by dying in Jerusalem and becoming the suffering servant king of Isaiah 53 who dies for the sins of Israel.

This shocking idea gets explored further in the next story, as Jesus goes up a mountain with three of his disciples. Jesus is suddenly transformed before them, they’re enveloped in a cloud of God’s presence, and they hear the announcement, “This is my chosen Son” (Luke 9:35). Moses and Elijah, the two other prophets who encountered God’s presence and voice on a mountain, are present as well (Exod. 19-20; Exod. 1 Kgs. 19). Luke tells us that they talk together about Jesus’ “exodus” that he was about to fulfill in Jerusalem (Luke 9:31), an obvious reference to the Exodus story.

Luke is portraying Jesus as a new Moses, who will lead his newly formed Israel into freedom and release them from the tyranny of sin and evil in all its personal, spiritual, and social forms. But to do this, Jesus must journey to Jerusalem, which brings us to the second main section of Luke’s account.

Luke 9:51-19:27: Jesus’ Inclusion of Outsiders Scandalizes Leaders

In the large center section of the book (Luke 9:51-19:27), Jesus leads his newly formed Israel on a journey to Jerusalem for Passover (Luke 9:51). This part of the book of Luke consists mainly of Jesus’ teaching and parables given on the road to people he encounters, mostly his growing group of disciples. In this way, Luke portrays following Jesus as a journey in which you learn as you go along life’s path.

Jesus invites his disciples into his mission as he sends a wave of them to travel further ahead, announcing God’s Kingdom. Luke is showing us that being a disciple, from the beginning, meant participating in the Kingdom mission of Jesus and making it our own. As Jesus’ disciples come back, he starts to give various teachings about prayer (Luke 11:1-13) and trusting in God’s provision (Luke 12:1-12). It’s in this section of Luke that Jesus talks about money, possessions, and generosity more than anywhere else (Luke 12:13-31; Luke 12:16; Luke 18:18-30). If following him is truly like being on the road, it should produce a minimalist mentality, creating a freedom from possessions that allows for radical generosity.

Another key theme in these chapters is Jesus’ continued mission to the poor. As he travels, Jesus continues to form his new Israel. He encounters people who are sick or blind, Samaritans (ancient enemies of the Jewish people), and, famously, Zacchaeus, a Jewish man who headed up tax collection for the Romans. All of these people meet Jesus and are transformed by their encounter, choosing to join his Kingdom community, which Jesus describes as a great banquet party. He’s here to “seek and save the lost” (Luke 19:10), and so he celebrates when people discover the mercy of God.

Not everyone at the party is happy, however. Luke includes multiple stories of Jesus at banquets with Israel’s leaders. These quickly become heated debates in which Jesus confronts their pride and hypocrisy. These contrasting banquet parties are captured most memorably in Jesus’ parable of the prodigal son (Luke 15:11-32), about a father who had two sons. The younger son was foolish, ran away, and squandered his inheritance. This son comes back repentant, however, and his father forgives him and throws a huge party to celebrate this “son who was lost, but now is found!” But the older brother is angry and resents his father’s generosity to this undeserving son.

In this famous parable, Jesus is explaining his mission to the leaders of Israel. His Kingdom parties represent God’s joyous welcome of every kind of person into his family. The only entry requirement is humility and repentance. In other words, this parable highlights the tragedy of Israel’s leaders, who reject Jesus and his Upside-Down Kingdom community.

Luke 19:28-24:53: Confrontation, Crucifixion, and Resurrection

As this resistance to Jesus ramps up and he finally arrives in Jerusalem for Passover (Luke 19:28-44), Jesus weeps as he nears the city. His disciples hail him as the messianic King, but the religious leaders denounce him. Jesus knows that their rejection of his Kingdom of peace will set Israel on a road of resistance and rebellion against the Roman empire, which will eventually bring about the city’s downfall.

It’s this looming destruction that Jesus symbolically enacts as he storms into the temple and runs out the animal sellers, bringing a halt to the sacrificial system. He says that this place of worship has become a “den of rebels” (Luke 19:46), and it will be destroyed. This action generates a whole series of debates between Jesus and Israel’s leaders, all leading up to Jesus’ prediction that Roman armies will one day surround the city and desolate it and the temple, all within a generation.

With that, Jesus retreats with his disciples to celebrate the Passover meal, the annual symbolic meal that retells Israel’s liberation from slavery through the death of a lamb. Jesus turns the meal’s bread and wine into new symbols about a new exodus. His broken body and shed blood will bring liberation for Jesus’ renewed Israel.

After the meal, Jesus is arrested and examined before the Jewish leaders. He is soon put on trial as a person claiming to be king, and here Luke emphasizes Jesus’ innocence. Pilate, the Roman governor, claims that Jesus is innocent three times before giving in. Even Herod, the ruler of Galilee, finds nothing for an accusation against Jesus. Despite this, the religious leaders and their persistence finally compel Pilate to have Jesus crucified.

Even during his painful death, Jesus embodies the love and mercy of God that he taught so much about. He offers God’s forgiveness to the soldiers as they crucify him (“Father forgive them,” Luke 23:34). Later, one of the criminals being executed alongside Jesus realizes who he truly is, saying, “Remember me when you come into your Kingdom” (Luke 23:42). Jesus’ final words are an offer of hope to this humiliated criminal. “Today you will be with me in paradise” (Luke 23:43). With this last act of generosity and kindness, Jesus dies.

His body is placed and sealed inside a tomb, but on the first day of the week, some of Jesus’ disciples come to the tomb and find it empty. Two angelic figures are there, who inform them that Jesus is alive and risen from the dead. The disciples leave, minds blown.

At this moment, Luke tells one of the most beautiful stories (Luke 24:13-32). Two of Jesus’ disciples are leaving Jerusalem for a town called Emmaus, heartbroken over Jesus’ death. Suddenly, Jesus is there walking alongside them, but they don’t recognize him. He asks why they’re sad, and they go on to talk about how they had hoped Jesus was the one to redeem Israel. But he obviously wasn’t, given the tragic fact that he’s dead. It was all for nothing. Later, as they’re having a meal, Jesus breaks the bread for them as he did at the Passover meal, and it��’s in that moment that they finally recognize him!

Luke tells this story to make a powerful point about following Jesus. When a person imposes their agenda and view of reality onto Jesus, he remains invisible and unknown to them. We will only see and know the real Jesus when we submit ourselves to his Upside-Down Kingdom, epitomized in his broken body on the cross that was offered in self-giving love.

The book of Luke’s concluding scene is set around yet another meal. Jesus appears before his disciples and explains to them, using the Old Testament Scriptures, how these events were all part of God’s plan. The Messiah would become Israel’s king by suffering and dying for their sins and conquering their evil with his resurrection life. Just as Simeon the prophet promised all the way back in Luke 2, Jesus’ Kingdom was always meant to move outward. So Jesus tells the disciples that God’s forgiveness must now be announced to all the nations by inviting people to follow him.

But for the moment, Jesus tells his disciples to wait in Jerusalem for the coming of the Spirit, who will empower them for this new mission. And this, of course, compels you to turn the page and keep reading into Luke’s second volume, the book of Acts.